Ferris Wheel History

|

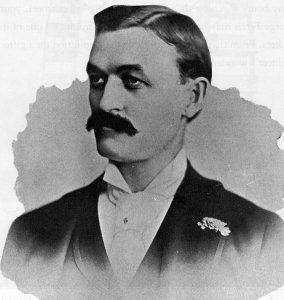

W.E. Sullivan’s destiny was forged forever by his encounter with the Great Ferris Wheel of the 1893 Columbian Exposition. William's visit to the Columbian Exposition in 1893 not only changed his life but would forever alter the amusement business. Some years later, he penned an account of his actions while at the Fair. |

|

By 1897, Sullivan had moved his family to Jacksonville, Illinois, and traveled for a St. Louis hardware firm, all the while continuing his plans to create a portable Wheel. He tried to get the parts for his Wheel built by the Jacksonville (later Illinois Steel) Bridge Company, but the management did not believe his ideas would work. They did agree to rent the plant and equipment to Sullivan for 15 cents an hour. With no other income available, the Sullivan's were eventually forced to mortgage their home to finance the project, against the persistent advice of Mrs. Sullivan’s parents. Machinist James H. Clements became interested in the project in 1899 and bought a one-third interest in it for one hundred and fifty dollars. In early 1899 Sullivan began drawings for his Wheel. These drawings led to the making of patterns in Crawford’s Mill and the pouring of castings at the A.W. Bambrook Foundry. On March 23, 1900, he secured the contract with the Jacksonville Bridge Company and the actual construction began April 14. The work progressed until May 12 when it was completed and erected in the company’s yard. The finished Big Eli® Wheel was forty five feet high and had twelve phaeton-type buggy seats for passengers. It was held together by five hundred and twenty one bolts and required six men and full day to erect it. The Wheel was powered by a one-cylinder Davis gasoline engine. The twelve seats installed on this first Wheel were actually modified buggy seats purchased from the Jacksonville firm of Hall Brothers. He obtained a permit from the City of Jacksonville, and paid a small fee to set up his Wheel and operate it in town. Once the Wheel had been successfully tested, it was dismantled, packed onto transfer wagons, hauled three-quarters of a mile to Central Park, and set up again. The Wheel was erected on the east side of the park between the curbstone and the south sidewalk. He premiered his creation on May 23, 1900. With a charge of five cents per ride, it grossed five dollars and fifty six cents that day, a very successful debut in a time when a dollar was a good day’s pay. He wrote of it in his diary, but never explained where that sixth cent came from. Speculation has suggested a child with only a single penny wanted a ride and Sullivan gave it to him for one cent. He continued to operate the Wheel on afternoons and evenings when the weather was suitable until the latter part of June. An important milestone was accomplished when Sullivan and Clements took their Wheel out of town for the first time. They set up the Wheel in the middle of a dirt street in Beardstown, Illinois, and ran it for a week during the Fourth of July celebration. During their stay, they camped in a tent pitched right next to the Wheel. Due to the rough element frequenting Beardstown in those days, they dug a hole in the road under their tent, placed pallets over the hole, and at night hid in it the money earned during the day. One of them would stand guard outside while the other dropped coins into the hole. When anyone came along, the man outside would whistle the tune “Annie Rooney” and the other stopped clinking coins into the hole until the coast was clear. After returning home, he did not immediately tell his wife about his success. He dumped the take out on the kitchen table and it totaled eighty three dollars. Both he and his wife cried, realizing they had finally proved the Wheel a successful venture. The Wheel was moved from town to town in railroad boxcars and transported to the operation site by horse-drawn hay racks or flat top wagons. It proved its mobility as it appeared at street fairs in Illinois, Missouri, and Indiana throughout the summer, ending its first run at the Free Street Fair in Veedersburg, Indiana. At the close of the first season, Clements bought Sullivan’s interest in the Wheel. Sullivan returned to Roodhouse and the following winter months were spent upgrading the design. In April, 1901, Sullivan was struck down with a severe case of inflammatory rheumatism which kept him bedridden and motionless for three months. Clements continued to operate the Wheel and Sullivan’s family lived off its percentage of the take. A recovery looked improbable until he contacted an osteopathic physician, who was able to set him on the road to recovery within minutes. An improved model was assembled in the fall of 1901 and opened for business on October 15 in Galesburg, Illinois, the birthplace of George Ferris. This Wheel greatly improved on the original design: Two hundred bolts had been eliminated, as had five hundred pieces of steel, one thousand and ninety six rivets, and the drilling of two thousand eight hundred and two holes. The seats had been reworked. The Wheel was forty feet high and was driven with a gear. The public reaction to this system was unfavorable and Sullivan did not experiment further with a gear drive. At the close of this second season, Sullivan sold his interest in the Wheel to Clements. The 1900-1905 were the “testing and improvement” periods. This also marked a serious legal challenge to Sullivan’s creation mounted by Troy, Pennsylvania manufacturer J.G. Conderman. A Wheel designed and constructed by Conderman was erected in 1899, but due to faulty construction had to be reworked the following year. He later received a U.S. patent and he instituted infringement proceeding against Sullivan, Clements, and other Wheel builders. The courts ruled in 1904 that the Wheel itself could not be patented and dismissed the suits. The last Conderman Wheel was built in 1905. The first three Wheels were built in different shops, and at each Sullivan tried to persuade the men in charge to construct a Wheel with completely interchangeable parts. There was just one workman who agreed it could be done. In 1905 Sullivan made working drawings of a Wheel with such interchangeable parts, a novel idea at the time. He rented a shop and secured tools which he operated with his Ferris Wheel engine. Sullivan proved his theory by building the first Big Eli® Wheel with interchangeable parts. There were no bolts used in the structure of the Wheel. There had been five hundred and twenty one in the first model. The new Wheel was socket and pin connected, lighter than the earlier models, compact when down, and was the realization of Sullivan’s dreams. On July 22, 1905, this Wheel was erected and operated for the first time. It grossed seventy four dollars and sixty cents the first day. In twenty weeks of operation in the fall of 1905 and fifteen weeks in the spring of 1906, it grossed eight thousand three hundred twenty three dollars and fifty five cents. It was a revelation to riding device owners and carnival men because it was quick to erect and easy to operate. |

|

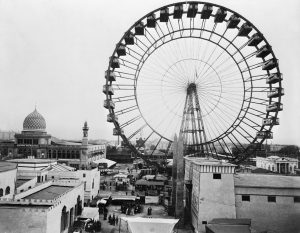

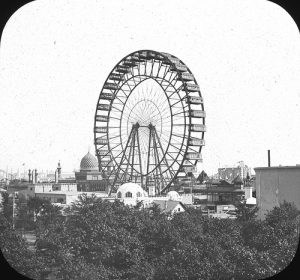

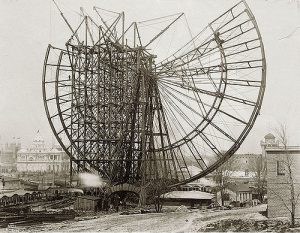

“I went to the Wheel and inquired of the ticket seller if they allowed visitors to examine the mechanism”, Sullivan wrote. “As well as I recollect, his answer was that if I bought a ticket, I could go in and examine it all I wanted. Buying the ticket, I went into the enclosure, went around to the man operating the levers, told him I would like to examine the entire machine as much as possible. He very kindly consented to let me examine it and I stayed with him probably an hour or more. I examined the engines, the driving mechanism of the Wheel in fact, examined the entire structure all I could from that point. Then I got in line with the passengers and entered a car, and while riding around the Wheel I examined it all I could through the windows of the car.” He returned to his home in Roodhouse, Illinois, and told his wife, “I have discovered the machine I want to design and build - a portable Ferris Wheel.” Noticing his wife was smiling, he added, “Well, don't you think I can build it?” “Sure, you can build it,” she replied. “You have built most anything mechanically you have set your mind to, but when you get it built, what are you going to do with it?” What, indeed! |